28 May 2019

· My four-week trip to the Eighty Years’ War ·

In 1574, the Dutch Revolt was six years old. I was twenty-four, in Flanders, in a hurry. On a mission. Probably nothing you’ve read about, if you’ve read anything. Most of the little that’s been written is ridiculously wrong.

For untruth is untruth though ever so old, and time cannot make that true which was once false.

Something like that. [1]

Time for the truth, never so old but told anew.

![]()

George Gascoigne

George Gascoigne

(~1537 – 7 Oct 1577)

FOR MARS AS WELL AS MERCURY

![]()

Early June 1574

George Gascoigne was in trouble.

Not his typical litany of woes– disinheritance, default, affray, marrying a woman who already had a breathing husband. Those were temporary inconveniences, this was trouble.

George was across the North Sea in the Low Countries, a captain in a contingent of five hundred English volunteers. They were fighting in support of insurgents led by Willem the Silent of Orange, against the army of the Spanish Habsburg king Philip II. At the end of May the Englishmen were forced to abandon a fort outside Valkenburg, near Leiden. The Leideners, distrusting their erstwhile allies, denied them safety inside the town walls, hanging them out to dry with no option but surrender. When the news reached England, no one knew what had become of them.

The problem, paradoxically, was that England and Spain were not at war. Elizabeth looked through her fingers at English free-lancers who fought with the Dutch against Spanish rule, but she maintained her official deniability. Because of this policy policyless, the prisoners held no military status in the eyes of their captors. They could be put to death at any moment as foreign agitators, abettors of rebellion.

England couldn’t afford to hazard the status quo for these men. The threat of invasion in the name of religion was too great, the realm wasn’t ready. Even the captives knew that their fate was their own.

1562, 1567, 1572, 1574

After my father died in 1562, George Gascoigne was one of the hundred and forty horsemen who escorted me from Hedingham Castle in Essex to Cecil House in London, where I commenced my altered life as a royal ward. I was twelve, GG was twice that, or thereabout [2]. It was an early crossing of our paths, but our true friendship began five years later. At seventeen I was sent to Gray’s Inn to learn the laws of the land I owned a lot of. George was there for the second time, after an extended run of inconvenience had interrupted his earlier studies. Chastened (somewhat), he had settled down (somewhat), returning not long before I arrived.

George was my first artistic friend, someone who shared my passion for poetry, drama, languages, the classics. Despite our age difference, we got on like twins. He was the role model I had longed for. Someone who could show me the way in the new world of my adulthood. Someone who knew what my allowance should buy. Someone I liked, unlike my guardian

George was my first artistic friend, someone who shared my passion for poetry, drama, languages, the classics. Despite our age difference, we got on like twins. He was the role model I had longed for. Someone who could show me the way in the new world of my adulthood. Someone who knew what my allowance should buy. Someone I liked, unlike my guardian . Witty, wicked George ticked all the boxes. He had the year before translated Ariosto’s Supposes from the Italian, adapting it into the first prose comedy in English, arranging for its performance at the Inn. Though I wasn’t yet enrolled, I went to see it. It was so new. It was brilliant.

. Witty, wicked George ticked all the boxes. He had the year before translated Ariosto’s Supposes from the Italian, adapting it into the first prose comedy in English, arranging for its performance at the Inn. Though I wasn’t yet enrolled, I went to see it. It was so new. It was brilliant.

We doled out time to the Law and lavished the balance on the Muses. We hardly slept, as our chandlery bills attested. We taught each other what we knew, and learned from each other what we didn’t. The time flew. When our stays ended and our paths diverged, our bond held fast.

Now I must turn the accomplishment of several years into an egg-timer.

In 1572 George was again facing inconvenience. Barred from returning to a seat in Parliament for Midhurst, threatened with returning to a cell in prison for debt, he abandoned Mercury and his creditors in England, pinning his hopes on Mars across the sea.

I had inconveniences of my own. I was twenty-two, newly married to my bride of fifteen. Cecil, now Lord Burghley, was now my father-in-law. I was suing my livery to re-enter my estates, the ruinously expensive process that would terminate my wardship. Over at the Tower, my cousin Tom Howard, Duke of Norfolk awaited the executioner’s axe for his inability to resist the siren song of the Queen of Scots. Amid all these stirs I kept my friendship with George safe in my heart, among my chiefest jewels.

Jumping o’er two more years. Valkenburg fell, and George was in trouble.

Mid through Late June 1574

Once the prisoners were known to be alive, rescuing George became my only concern. I’d require cash for passage and horses and guides and bribes, but mortgages were easy to get. They would be repaid, so I figured, from Anne’s dowry, which Burghley still owed me after two and a half years. Fifteen thousand pounds, well above any amount needed to liberate George and redeem the loans. For reasons best explained in a footnote [3], the money was supposed to be waiting for me, in gold, in Dunkirk.

My wife objected, wailing. Her father objected, railing. Her Majesty objected, assailing. To all I was obdurate who were obdurate to my friend. I was the only man in Christendom who could deliver George Gascoigne. He would not perish because I chose not to bother.

On the second of July I crossed to Calais, prevailing.

I know there are no cannonballs. It’s only a map.

I know there are no cannonballs. It’s only a map.

Google Maps (initially)

The Spanish Threat

Elizabeth with her right and left hands,

Elizabeth with her right and left hands,

and two others holding her regalia.

Wellcome Collection![]()

![]() The Regnum Cecilianum was an oppressive regime under which many people suffered. I was one of them, and it is no exaggeration to say that Shake-Speare suffers still, directly. But there’s a difference between an ostensibly insular, autonomously-governed surveillance state, bad as that may be, and a subject state ruled by an expansionist foreign power who maintains political control with an army and doctrinal control with an Inquisition. The Low Countries were states of the second sort. The Dutch desired self-determination and were willing to go to war to get it. It took eighty years of fighting against the bloody constraint of Spain before their independence was assured.

The Regnum Cecilianum was an oppressive regime under which many people suffered. I was one of them, and it is no exaggeration to say that Shake-Speare suffers still, directly. But there’s a difference between an ostensibly insular, autonomously-governed surveillance state, bad as that may be, and a subject state ruled by an expansionist foreign power who maintains political control with an army and doctrinal control with an Inquisition. The Low Countries were states of the second sort. The Dutch desired self-determination and were willing to go to war to get it. It took eighty years of fighting against the bloody constraint of Spain before their independence was assured.

England wanted to avoid that fate. Those who governed the realm (that’s them in the picture) knew that an invasion would be attempted in due course, flying the flags of the Spanish king, the Roman pope, and the Scottish pretender queen. The fears at home were not unjustified. Philip and Pius (then Gregory) and Mary were all on record: Elizabeth had to go.

We had to prepare. Not only with culverins and race-built galleons to fire them from, but by re-examining who we were and why we’d be fighting. Our sense of English identity had taken a beating during the decades of Lancaster versus York, when nobles and their affinities split into factions of blood and self-interest (my rose-plucking fiction dramatic licence). After Bosworth, what Henry VII had begun to repair was rent again asunder when his son tore England from Rome. Young Edward then swung far to the Protestant side, Bloody Mary far to the Catholic. Elizabeth aimed for a via media, but few were satisfied. The widening rift became the breach through which our enemies could enter.

Elizabeth trusted her people to remain loyal to her, English first. Burghley called her naïve and slept poorly. Walsingham didn’t sleep at all.

![]()

Intermedio Primo

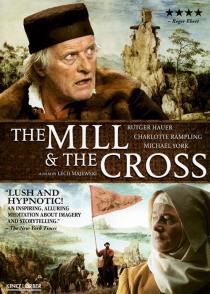

Many of my memories of Flanders returned to me in one unsettling jolt when I saw Lech Majewski’s 2011 film The Mill and the Cross, which recreates The Procession to Calvary painted in 1564 by Dutch artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder. From the film’s first scene I was transfixed. It conducted me like an electric shock back to that place and time.

First the painting. Click on the image for an enlargement. The caption links to others. The work’s size is 124×170 cm, 49×67 in. It’s big.

· The Procession to Calvary ·

· The Procession to Calvary ·

by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1564

Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

also 2018 KHMV Bruegel exhibit,

Wikimedia Commons

![]() Next, a bit of analysis and historical context.

Next, a bit of analysis and historical context.

![]()

![]() The red-garbed horsemen are described in the video as Spanish soldiers. It’s an understandable mistake, but they were not cavalry. Red Riders, the Roode Rocx, were Philip’s mounted militia, unconnected to the armyWorld War II analogue: SS, not Wehrmacht. The comparison is more apt than you’d like to think.. They were as notorious for their tactics as for their tunics; both are featured in The Mill and the Cross. Nor were all Roode Rocx Spanish. Many came from WalloniaModern Belgium remains divided between northern Dutch-speaking Flemings and southern French-speaking Walloons. The area around Brussels is officially bilingual.

The red-garbed horsemen are described in the video as Spanish soldiers. It’s an understandable mistake, but they were not cavalry. Red Riders, the Roode Rocx, were Philip’s mounted militia, unconnected to the armyWorld War II analogue: SS, not Wehrmacht. The comparison is more apt than you’d like to think.. They were as notorious for their tactics as for their tunics; both are featured in The Mill and the Cross. Nor were all Roode Rocx Spanish. Many came from WalloniaModern Belgium remains divided between northern Dutch-speaking Flemings and southern French-speaking Walloons. The area around Brussels is officially bilingual. to the south, mercenaries eager to tyrannise their neighbours for Spanish silver. I had a close encounter with a drunken Walloon in his red tunic when I was trying to get around Ghent unnoticed. I didn’t forget.

to the south, mercenaries eager to tyrannise their neighbours for Spanish silver. I had a close encounter with a drunken Walloon in his red tunic when I was trying to get around Ghent unnoticed. I didn’t forget.

Bruegel used his talents for observation and synthesis to add political relevance to his sacred story. Flanders was not Calvary, but the shift in location and time, the analogy of persecution for a new faith, and the substitution of Spain for Rome combined to make an ironic, prescient statement about the conflict that was only beginning to begin in 1564.

If you live in the US, Canada, Australia, or Mexico, you can stream The Mill and the Cross at no cost at TubiTV (as of this posting, at least). You don’t even need a login. If you’re in Europe you can’t, thanks to the GDPR. In any case you should hunt down the Blu-ray disc and play it on a large screen. This film needs high-end hardware to do it justice.

If you live in the US, Canada, Australia, or Mexico, you can stream The Mill and the Cross at no cost at TubiTV (as of this posting, at least). You don’t even need a login. If you’re in Europe you can’t, thanks to the GDPR. In any case you should hunt down the Blu-ray disc and play it on a large screen. This film needs high-end hardware to do it justice.

The Mill and the Cross doesn’t feature conventional leading characters within a well-defined plot arc. There isn’t much dialogue. Majewski gave Bruegel’s vision breath and a beating heart, but it’s more a series of animated tableaux than a linear story. Bruegel himself and his patron Nicolaes Jonghelinck serve as the connectors. Bruegel is played by Dutch actor Rutger Hauer, Jonghelinck by Michael York. York began his film career in 1967 with one of my roles, has played a goodly number of others, and in 2000 wrote a book on Shakespearean acting. This is the spot where I encourage you to listen to him speak of his Doubt About Will, the man from Stratford.

The lack of Instagram photography in my day means that opportunities are rare when I can say This is what I saw, this is what it looked like, this is what was happening. Something visual that I experienced, or near enough, more than four hundred years ago. The Mill and the Cross is a film about a painting of a relocated Crucifixion made ten years before I was in the area. Unlikely as it sounds, this is one of those opportunities. The Bruegel video calls The Mill and the Cross a strange movie. I call it magnificent.

![]()

Mid through Late July 1574

I knew I’d have to push my horses hard and myself harder to get beyond Flanders and north through the real fighting, if I was going to reach George in Holland in time to save him. What I didn’t know was that the new Governor-General of the Spanish Netherlands, Luis de Requesens, had sent Bernardino de Mendoza to London to meet with Elizabeth. On 17 July, in a thoroughly planned spontaneous gesture, Spain cast the English prisoners in a political set-piece. Mendoza, to promote himself as a trusty fellow and Requesens as less bloodthirsty than his predecessor the Duke of Alva, promised to obtain the release of the captives, in Elizabeth’s name. The men would live. Bess ex machina.

Tom Bedingfield told me all this when he caught up with me in (Zalt)Bommel. Wiliest great boar I ever tracked were his first laughing words. I never did make the last fifty miles to the royal prison at Haarlem where the English officers were held. Elizabeth wanted me safely home without delay, and since Tom assured me that George was safe I didn’t give him a hard time. I can’t say I was the best of company. All the livery advances, safe conducts, and payoffs I had laid out in anticipation of returning with George in haste and secrecy were now pointless. More to the point, they were gone. The chimeric Dunkirk dowry meant vaarwel to my mortgages. That’s where the money went, not into the hands of exiled Catholic plotters. My trip had nothing to do with the Earl of Westmorland and his sorry lot; I never saw them. Some people will believe anything.

I didn’t put our return trip on the map. I believe we shipped out of Rotterdam, but I was soaking my frustrations in a lot of genever so the memories are blurry. Tom hired our passage and poured me on board, and we landed at Dover just before month’s end.

The captive soldiers were soon repatriated. Requesens held the officers a bit longer, to insure that a Spanish fleet heading east through the Channel would be allowed to resupply safely in English ports. George was home in October with a crumpled draft of The fruites of Warre in his pocket, written during his internment. He hadn’t abandoned Mercury after all.

Trusty Mendoza was later discovered up to his eyeballs in the Throckmorton plot, yet another attempt to replace Elizabeth with Mary Stuart. The ambassador was booted from the country.

![]()

Also in 1574

In Warwickshire, young Willy Shakspere was a lad of ten. He might have been at his hypothetical desk in his hypothetical classroom, head bent over his hypothetical book, giggling at Latin wordplay in the comedies of Plautus. Or he might have been mired in his own war of rebellion, fighting against the fowl forces of occupation scratching for grubs on the high ground of his father the glovemaker’s illegal dunghill. Who can say. [4]

![]()

Intermedio Secondo

The 1935 film Carnival in Flanders is set in 1616 in the Flemish town of Boom, today a suburb of Antwerp. The Twelve Years’ Truce in the Eighty Years’ War began in 1609, thus 1616 was a time of reduced violence, though not peace.

When told that Spanish troops will billet in the town, Boom’s young aldermen want to give them the benefit of the doubt in the name of commerce. “Passing soldiers bring passing trade” they suggest. Distressed, the older aldermen remind their juniors of the depredations of the Army of Flanders a generation before. The film flashes back forty years to the Sack of Antwerp, which took place over 4-6 November 1576.

Carnival in Flanders, by Flemish director Jacques Feyder, is (believe it or not) a proto-feminist comedy of manners, a bourgeois cousin to Lysistrata. The flashback to the Sack stands in stark, intentional contrast to the rest of the film’s ebullient humour. The scene is a reminder of an atrocity not forgotten by Flemings like Feyder, even after three and a half centuries.

![]()

November 1576

Google Arts and Culture has historical images of the Sack, also called the Spanish Fury at Antwerp, from Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum and elsewhere. Some of the pictures look just like Feyder’s flashback.

What prompted this rampage? Deficit spending. Chronically insolvent from his simultaneous wars against Protestantism in the west and the Ottoman Empire in the east, Philip declared Spain bankrupt at the end of 1575As he had done in 1557, 1560, and 1569, and would do again in 1596. All the stolen treasure in the New World was not enough.. Unpaid Spanish soldiers turned repeatedly to murder and pillage: the Spanish Fury. Eight thousand citizens were killed in Antwerp alone.

What prompted this rampage? Deficit spending. Chronically insolvent from his simultaneous wars against Protestantism in the west and the Ottoman Empire in the east, Philip declared Spain bankrupt at the end of 1575As he had done in 1557, 1560, and 1569, and would do again in 1596. All the stolen treasure in the New World was not enough.. Unpaid Spanish soldiers turned repeatedly to murder and pillage: the Spanish Fury. Eight thousand citizens were killed in Antwerp alone.

An eyewitness account of the Sack of Antwerp was provided by an Englishman who was in the city on government business when it took place. That Englishman was George Gascoigne.

George survived the turmoil and returned to London on 21 November. He reported to the Privy Council, then quickly published his account in a pamphlet, 1576’s analogue to blogging. The spoyle of Antwerpe, Faithfully reported, by a true Englishman, who was present at the same. Novem 1576. Seene and allowed. The internet is a gift.

The spoyle of Antwerpe reads like vintage Georgian prose, colourful in detail though his death toll of 17,000 is exaggerated. It is not without moments of humour, despite its grim subject. But while GG saw the Sack and lived to tell the tale, the tale he told was a brazen hoax. Witty, wicked George lifted nearly all of his Faithfull report from an anonymous Dutch pamphlet he brought home with him. Lock, stock, and most of the barrel. This explains why he didn’t put his name on his version, forgoing the credit he was usually quick to claim.

GG was more than capable of writing his own narrative, so why cheat? Because honest reporting would have taken too long and cost too much. Penurious George was always stone broke or worse. He knew he had a valuable exclusive in his hands, but only if he could turn it into cash before the hot story cooled off. This wasn’t Art, this was Economics.

If you read the hoax, read this article in the journal Dutch Crossing that describes how he did it. Audacity, thy name was Gascoigne. I can confirm for the author that George had no need to filch from a French translation, he could filch quite well from the Dutch original.

Keep in mind that prior to the enactment of the Statute of Anne in 1709-10 there was no protection in law for authorial copyright. Sharp practice like George’s was not uncommon. Anyone could purchase or purloin work written without attribution or even with it, or from a foreign source; fiddle with it a little perhaps, then sell it at a handsome profit, anonymously, pseudonymously, or poaching the credit under his own name. A noteworthy example of the third case comes to mind, involving a Warwickshire glover’s son who did some lucrative business selling plays he didn’t write.

George’s CV included (among much else) the first prose comedy in English, the first instructional manual for aspiring English poets, first-person disaster journalism, and the misuse of intellectual property before the concept was ever defined. He lived ahead of his time, and he died the same way. Eleven months after Antwerp he succumbed to an illness, barely forty (probably). His unwritten contributions to English literature can only be imagined. I mourned deeply for him for the rest of my life.

![]()

August 1574

Elizabeth did not angrily dispatch Tom Bedingfield to haul me back to England ‘under threat of heavy penalties’. What a mendacious barrow of butcher’s offal. Tom was no bail bondsman, he was a trusted friend and a fellow writer, much as George was. Tom and I had broken lances together in the joust, and in ’73 I had arranged for the publication of his English translation of Cardanus Comforte —later (and still) known as ‘Hamlet’s book’— which he dedicated to me. Having my confidence was crucial, it was why Elizabeth gave him the job. Few men could run me to ground in that hostile land and then say You can stop here, George won’t be harmed, he’ll be released soon, let’s go home, whose word I would take.

The non-offal truth was this: once Bess had Mendoza’s word that George and the others were safe, her objective was to get me out of harm’s way, preserving what she could of my purse as well as my person. She knew that the longer I was gone, the less likely any of my borrowed funds would return with me. She knew nothing of the dowry/kickback, which would have cost Burghley his job, his title, his fortune, and probably his head had she learned of it.

Tom and I rode from Dover back to London, where I restored myself with hot baths, good suppers, and sound sleep. I arranged for some new apparel that proclaimed the man, then at mid-month I travelled with my querulous father-in-law to meet the royal progress in the West Country.

![]()

Burghley harangued me the entire way, barely pausing to inhale. I was so bored I counted the time in my head: his record was thirty-two allegretto beats between breaths. I kept hoping he’d pass out. The incessant spate of rebuke and criticism and anxiety went on and on and on for a hundred plodding miles A poor rider with a bad seat, Burghley’s horses only walked. He preferred mules. beneath the unrelenting sky with no genever to take the edge off. He had rehearsed his rant in a groveling letter to Walsingham, already with the queen. One, endless, sentence gives you the idea:

A poor rider with a bad seat, Burghley’s horses only walked. He preferred mules. beneath the unrelenting sky with no genever to take the edge off. He had rehearsed his rant in a groveling letter to Walsingham, already with the queen. One, endless, sentence gives you the idea:

![]() I beseech you to impart such parts of this my scribbling with my Lords of the Council with whom you shall perceive Her Majesty will have to deal in this case, that not only they will favourably reprehend him for his fault, but frankly and liberally comfort him for his amends made both in his behaviour beyond seas and in his returning as he hath done, and beside this that they will be suitors to her Majesty for him, as noble men for a noble man, and so bind him in honour to be indebted with goodwill to them hereafter, as indeed I know some of them hath given him good occasion, though he hath been otherwise seduced by such as regarded nothing his honour nor well doing, whereof I perceive he now acknowledgeth some experience to his charge, and I trust will be more wary of such sycophants and parasites.

I beseech you to impart such parts of this my scribbling with my Lords of the Council with whom you shall perceive Her Majesty will have to deal in this case, that not only they will favourably reprehend him for his fault, but frankly and liberally comfort him for his amends made both in his behaviour beyond seas and in his returning as he hath done, and beside this that they will be suitors to her Majesty for him, as noble men for a noble man, and so bind him in honour to be indebted with goodwill to them hereafter, as indeed I know some of them hath given him good occasion, though he hath been otherwise seduced by such as regarded nothing his honour nor well doing, whereof I perceive he now acknowledgeth some experience to his charge, and I trust will be more wary of such sycophants and parasites.![]()

– Burghley to Walsingham, 3 August 1574

He was much, much worse to hear than to read.

I was to confess my sins and receive royal absolution in the port city of Bristol, amid mock naval battles celebrating the queen’s visit and the signing of the Convention of Bristol on 21 August. The treaty was an important, tension-reducing diplomatic and trade agreement between England and (wait for it) Spain.

After what I had just been through in the Low Countries I was in no mood to party with Spaniards. It was hard to watch them dispensing smiles and gifts in Bristol when I recalled what their brethren were dispensing in Flanders. And I couldn’t very well ask anyone about Burghley’s kickback in those surroundings.

Bristol, dependent upon Spanish shipping and trade for its commercial prosperity, showed its civic gratitude to the Lord Treasurer with presents of sack, claret, and sugar. Not much of the sack made it back to Theobalds.

![]()

Why did Burghley care so much about me? I may have been the first royal ward who became his charge, but I wasn’t the last. He supervised the upbringing and the finances of half a dozen or so orphaned earls and barons in the years following my ride to Cecil House in 1562.

Was it a surrogate father’s paternal feeling for his foster son? Please. He lacked affection even for his own sons, though he was fond of his daughters. He and I were ever chalk and cheese. Was it my wealth? He took full advantage of that while he could (though Leicester was the greater thief), but I was now of age and not so easy to fleece. So why didn’t he get an annulment for Anne, start over with a less recalcitrant son-in-law? In 1574 she was still only seventeen, and young for her age. Alas, she loved me, or she loved the idealised version of me that lived in her girl’s heart. Sadly for her it bore little resemblance to my living self.

Even so, Anne’s love for me was not the brake on her father’s actions. What must be understood is that William Cecil’s greatest desire, unachieved though he was the most powerful man in the realm, was to engraft a scion from his family tree onto the rootstock of the high nobility. He had run my life for a dozen years to achieve one end: to complete the rise of the Seisylls from his own grandfather, third son of a Welsh borderman, through himself to a de Vere grandson owning blood that crossed with the Conqueror. None of his later heirs-in-residence ever came close to my ancestry, and Burghley was never one to settle for half when he could take the whole. The answer to the question is his ambition, implacable and unsparing.

Even so, Anne’s love for me was not the brake on her father’s actions. What must be understood is that William Cecil’s greatest desire, unachieved though he was the most powerful man in the realm, was to engraft a scion from his family tree onto the rootstock of the high nobility. He had run my life for a dozen years to achieve one end: to complete the rise of the Seisylls from his own grandfather, third son of a Welsh borderman, through himself to a de Vere grandson owning blood that crossed with the Conqueror. None of his later heirs-in-residence ever came close to my ancestry, and Burghley was never one to settle for half when he could take the whole. The answer to the question is his ambition, implacable and unsparing.

In his mind, the sins I committed with my run to Flanders were threefold: I left with a pile of borrowed money and returned with none, I ignored a royal command, and (worst by far) I put myself into real physical danger which threatened the future existence of his unconceived grandson. And I committed these sins for no better reason than to save the life of one of my sycophantic, parasitic poet pals. The old man was beside himself.

![]()

Raging Ruler Requires Runaway’s Rapid Return, Repentance was never more than a fiction based on a contrivance. Theatre. What took place between Bess and me at the Great House in Bristol was not a dressing-down but a private meeting of minds, followed by an interlude staged for Burghley’s benefit. To calm his jangled nerves, the Queen and I played parts in a scene consisting of a bowed head over a bent knee, a wrist gently slapped with a caress, an apology made and accepted, a hand extended and kissed. A performance à deux for an audience of one.

It is true that Her Majesty was not most happy when I went AWOL, but at least she understood why I did it. Burghley the parvenu peer never had the slightest grasp of the obligations of honour that came with noble birth. Blood will tell. I still have moments when I regret not exposing his corruption in the treaty negotiations, but the Lord Treasurer was far too cunning to leave me with any way to prove what I knew. His entire career was an exercise in covering his tracks, making the record, his record, look good. Whistle-blowing wouldn’t have procured Anne’s dowry in any case. (Don’t ask.) And for all that I loathed his hypocrisy and detested his methods, I wasn’t heartless enough to denounce the beloved father of my guileless young wife. I’m sure he knew that, and relied on it.

![]()

My Flanders trip had a significant influence on what would become the history plays, but when I look back on it from this temporal distance, what matters most is that it was the harbinger of Italy, the catalyst. If I hadn’t first flown to Flanders without Elizabeth’s permission, I doubt I’d have made it to Italy later, with it. As I talked with her at Bristol —describing my perils and adventures, answering her questions, offering opinions, making her laugh with a couple of slightly tall tales— the scales fell from her eyes. She could finally see what I already knew: I needed a change, a reprieve from my own life.

Six months later I was back in France, on my way to Venice. This time I was rescuing myself.

![]()

![]()

[1] The original quote is:

- …for truth is truth though never so old, and time cannot make that false which was once true…

I wrote that to my former brother-in-law Robert Cecil, at the beginning of May 1603. See this PDF [oxford-shakespeare.com] for a transcription of the entire letter, which concerns the long-delayed royal restoration of de Vere rights to the keepership of Waltham Forest.

[2] George’s age was something of a mystery. Whatever it was he didn’t look it, but he never wanted to reveal his years and by so doing admit to how much of his candle he had burned up with his wild living. Most sources guess a birth year ranging from 1528 to 1537. Ward proposes a date as late as the early months of 1542, based on the inquisition post mortem of George’s father. That would make him only eight years older than me, which I think is too young, especially as he sat in Parliament in 1558 and 1559. I put him at 12-14 years older than me, birth year 1536 to 1538. It never mattered enough for me to press him on the subject.

[3] The article Burghley’s Bribe, De Vere’s Dower? in the Sources below has more details, but TL;DR: the Lord Treasurer of England was conspiring to pay his daughter’s dowry with gold he’d been promised as a kickback by a Spanish agent, in return for better terms for Spain in the negotiations that led to the Bristol trade treaty. Burghley’s scheme was for me to take all the risk by collecting and transporting my own money, while he kept his hands and his reputation clean at home. Of course something was rotten in the city of Dunkirk; when I got there no one knew anything about any gold. I couldn’t stay to investigate, I had to get to George.

[4] I’m aware that Johannes Shakyspere suum illicitum sterculinium fecit in MDLII, a dozen years before his boy was born. (The original Stratford court citation calls the dungheap a sterquinarium, but sterculinium is better Latin.) John had presumably cleaned up his smelly mess by MDLXXIV, since no additional fines in the town records have been discovered. I’m not letting it spoil my anecdote. Twelve years too late is the same sort of self-serving, incorrect temporal shift that Stratford likes to impose upon my plays. At least I know when I’m joking.

John Shakspere’s public reprimand comes down to us from the National Archives by way of the Shakespeare Documented [sic] exhibition and website, put-on by the Folger. I was amused to note the writer of this obsequious apologia for the forbidden midden of Shakspere père. A man I’m accustomed to finding behind a poison-filled pen aimed directly at me, Professor Emeritus (of English, not history) Alan Nelson is the cited source for most of the information in my hostile Wikipedia entry. He is the credited writer of my malignant ODNB entry. He is the author of a monstrously adversarial biography so slanted and slipshod that it can’t stand upright. There’s more, but that’s more than enough. His malicious antipathy, extraordinary even by Stratfordian standards, makes me wonder why the not-so-gentleman doth protest so much. There must be Arundel blood in his pedigree.

![]()

- Sources and Additional Reading/Viewing

- in no special order

- • Banner image: from Carnival in Flanders, 1935, directed by Jacques Feyder. French title La Kermesse héroïque.

The film [tcm.com] has an interesting [nytimes.com] and even controversial [wikiwand.com] history, both before and after the Second World War. François Truffaut hated it. Chacun à son goût.

Streamable video at rarefilmm.com, French with English subtitles

- • The Mill and the Cross [book review at artsjournal.com]

- · by Michael Francis Gibson

- · University of Levana Press, 2012 edition, paperback, 156 pages

- The original 2001 edition of this book inspired Majewski to make his film, which he and Gibson co-wrote. This edition includes a great many close-up images from the painting, and what would have been a fine two-page reproduction of the whole thing, except that the binding almost swallows Jesus entirely, and everything else near the vertical center of the painting. It’s an unforgivable crime against Art that the publisher didn’t make it a fold-out.

- Also included are location photos that Gibson took during the film’s shooting in 2008. He was given a tiny part, but it fell to the cutting room floor. Gibson died in 2017, so now it’s sad that he’s not in the film. His ability to communicate meaningfully in words about visual art explains why he was such a respected critic. This portion of his preface was a surprise that made my day:

![]() [I was] distressed at the thought that very few people would ever be allowed close enough to the painting to appreciate Bruegel’s surprisingly expressionistic brushstroke, and with it the virtuosity, wit, and humanistic scope of an artist whom I have come to regard as the true Shakespeare of Flanders.

[I was] distressed at the thought that very few people would ever be allowed close enough to the painting to appreciate Bruegel’s surprisingly expressionistic brushstroke, and with it the virtuosity, wit, and humanistic scope of an artist whom I have come to regard as the true Shakespeare of Flanders.![]()

- • The Life and Writings of George Gascoigne: With Three Poems Heretofore Not Reprinted [archive.org]

- · by Felix Emmanuel Schelling

- · Ginn & Company, Boston, 1893, 131 pages

- • George Gascoigne: Elizabethan Courtier, Soldier, and Poet [books.google.com]

- · by C T Prouty (Charles Tyler)

- · Columbia University Press, New York, 1942, 351 pages

- · Reprint: Benjamin Blom, New York, 1966, 351 pages

- • A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres [books.google.com]

- · by George Gascoigne

- · edited by G W Pigman III

- · Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2000, 781 pages

- • A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres, From the Original Edition of 1573 [archive.org]

- · by George Gascoigne

- · (1st ed.) Bernard M Ward, 1926, (2nd ed.) Ruth Loyd Miller, 1975

- · Kennikat Press, Port Washington NY for Minos Publishing, Jennings LA, 1975, 398 pages

- • Representing War and Violence: 1250-1600 [books.google.com]

- · edited by Joanna Bellis and Laura Slater

- · Boydell Press, 2016, 218 pages

- · Chapter 8, Tudor Soldier-Authors and the Art of Military Autobiography, by Matthew Woodcock

- • Certayne notes of instruction in English verse… [including] George Whetstone’s A remembraunce of the well imployed life, and godly end, of George Gascoigne Esquire [archive.org]

- · by George Gascoigne, preface by George Whetstone

- · edited by Edward Arber

- · London, 1869, 132 pages (contents written 1575-1577)

- • The Statute of Anne, London, 1710 [copyrighthistory.org]

- · from Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), L Bently and M Kretschmer, editors

- · Faculty of Law, University of Cambridge

- • “Shakespeare” By Another Name: The Life of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, the Man who was Shakespeare [Amazon US | UK]

- · by Mark Anderson

- · Gotham Books/Penguin Group USA, 2005, hardback, 640 pages

- · also paperback, audiobook, and ebook formats

- • Burghley’s Bribe, De Vere’s Dower? [PDF] [shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org]

- · by Mark Anderson with Roy Wright (Tekastiaks)

- · Shakespeare Matters, 2003, Vol 3 No 1, pages 25-27

- Mark always impresses me with his research. This newsletter from the Shakespeare Fellowship (a progenitor of the SOF) also contains a review and commentary about the monstrous Nelson biography mentioned in Note 4 above.

- • Surveillance, Militarism and Drama in the Elizabethan Era [books.google.co.uk]

- · by Curtis C Breight

- · Macmillan Press (London), St Martin’s Press (New York), 1996, 348 pages

- · ebook edition [Google Play Books]

- • The Rise of the Dutch Republic, Volume II [books.google.com]

- · by John Lothrop Motley

- · Alexander Strahan & Company, Edinburgh, 1859

- • Anonymous SHAKE-SPEARE [anonymous-shakespeare.com]

- · website by Kurt Kreiler

- · 7.2.2. George Gascoigne, The Fruites of War

- · 7.2.3. Oxford in Flanders, July 1574

- • [Re-Posting] Reason 11: Oxford’s Prefatory Letter for “Cardanus Comforte” of 1573 [hankwhittemore.com]

- · Hank Whittemore’s Shakespeare Blog, 22 October 2017

- • Queen Elizabeth I’s Progress to Bristol in 1574: An Examination of Expenses [utoronto.ca]

- · by Francis Wardell

- · Early Theater, 2011, Vol 14 No 1, pages 101-119

- • George Gascoigne [shu.ac.uk]

- · edited by Stephen Hamrick

- · Early Modern Literary Studies 14.1/Special Issue 18, May 2008

- · in particular, Introduction: ‘Thus Much I Adventure to Deliver to You’: the Fortunes of George Gascoigne by Stephen Hamrick

- • Gascoigne’s The Spoyle of Antwerpe (1576) as an Anglo-Dutch text [tandfonline.com]

- · by Raymond Fagel

- · Dutch Crossing, Volume 41 Issue 2, 2017, pages 101-110

- • William Cecil, Baron Burghley on muleback [artuk.org]

- · attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, circa 1587

- · Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford